Sawbones, quacks and Old West doctors

By western author Nick Brumby

“Until the 1860’s—and in some sections long afterward—a frontier doctor was almost any man who called himself one.” – George Groh, American Heritage

The life of a doctor in the Old West was never dull. A typical day could see a ‘sawbones’ face death, disease, amputations, macabre surgeries, and even gunfights with competing physicians. All this from an individual who on average had little actual medical training or experience, and often did more harm than good. Despite this, people flocked to the sawbones for help. On the American Frontier, it was that or nothing.

The life of a doctor in the Old West was never dull. A typical day could see a ‘sawbones’ face death, disease, amputations, macabre surgeries, and even gunfights with competing physicians. All this from an individual who on average had little actual medical training or experience, and often did more harm than good. Despite this, people flocked to the sawbones for help. On the American Frontier, it was that or nothing.

Old West doctors were medical all-rounders, offering a wide array of medical services in an unforgiving environment. Frontier physicians had to be capable of diagnosing and treating everything from infectious diseases to traumatic injuries, as well as delivering babies, setting broken bones, performing amputations, and managing chronic illnesses with equal proficiency.

People commonly suffered injuries from mining accidents, cattle drives, violent confrontations, and the rigors of travel across difficult terrain. Wounds from gunshot or animal attacks often led to infections such as gangrene, which, before the acceptance of germ theory, were poorly understood and rarely effectively treated. Infectious diseases also posed a significant threat. Cholera, smallpox, tuberculosis, typhoid fever, and dysentery were widespread and could devastate communities with little warning.

Few physicians west of the Mississippi had qualifications or training. In fact, only about a quarter of physicians actually held any sort of degree at all, although many others learned the trade on their own by serving as apprentices. In many regions qualified doctors were so thin on the ground some settlers instead were forced to rely on snake oil salesmen, patent medicines and traveling ‘medicine shows’. Most anyone could hang a shingle and call themselves a doctor, with many bad physicians being labelled ‘quacks’ by their patients. But with the average life span between 1850 and 1880 being only 38 to 44 years of age (according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information), people took what they could get.

Despite these limitations, some Old West doctors worked at the cutting edge of medicine and were pioneers of modern medical practice. For example, Dr. George E. Goodfellow of Tombstone, Arizona, was among the first in the United States to use antiseptic techniques and perform advanced surgeries on gunshot wounds.

Despite these limitations, some Old West doctors worked at the cutting edge of medicine and were pioneers of modern medical practice. For example, Dr. George E. Goodfellow of Tombstone, Arizona, was among the first in the United States to use antiseptic techniques and perform advanced surgeries on gunshot wounds.

In boom towns, doctors set up offices wherever they could. In Tombstone, Dr. Goodfellow set up his first office in the Golden Eagle Brewing Company. After a fire burned down the building, Dr. Goodfellow moved to the Crystal Palace Saloon, the same building that housed the office of US Deputy Marshal Virgil Earp.

The lack of suitable doctor’s offices sometimes meant tensions ran high, with frontier physicians were sometimes protective of their territory. When Dr. Edward Willis moved to Hangtown, the town’s only other doctor, who had no medical training, challenged Dr. Willis to a duel. The risky move didn’t pay off for the untrained doctor, who ended up losing the duel and his life.

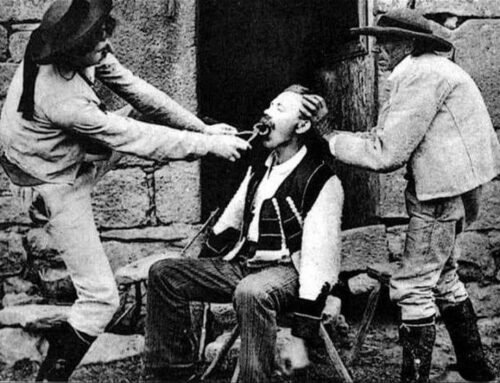

In rough and remote communities like miners’ camps, surgical tools were sterilized with carbolic acid or whisky, while the operating table could be anything from a tree stump to a whiskey barrel, with pain relief usually nothing more than a piece of leather to bite on. Many doctors instead visited patients at home, carrying everything from bandages, drugs, hot water bottles, knives, obstetrical instruments and a stethoscope, to saws and syringes in saddlebags or the classic leather ‘doctor’s bag’.

Common treatments included bleeding (sometimes using live leeches), cold baths, blistering agents, and other remedies that were worse than the ailments that they were meant to treat.

Amputation was a common surgical solution for limbs that were badly infected or crushed, but the lack of anesthetic pain relief and antiseptic techniques meant that this brutal procedure was risky and painful, Patients were often given alcohol or knocked unconscious to endure the pain, but trauma and pain were most often managed by cutting off the offending limb as fast as humanly possible. Despite the crude methods, amputation sometimes succeeded in preventing the spread of infection and saving lives.

In fact, the fastest leg amputation in history (using hand tools only) was by a surgeon during the 1840s – he took two and a half minutes from ‘go to woah’. The procedure was so fast the surgeon also managed to sever the fingers of his assistant and wound an observing doctor with his saw. The patient, the assistant and the observing doctor all subsequently died from gangrene or shock, making it the only operation in history with a 300% fatality rate.

Women and Native American healers played indispensable roles in frontier medicine. Women acted as midwives, nurses, and caregivers, administering home remedies and herbal medicines passed down through generations. Native American communities retained traditional healing practices based on herbal medicine, spiritual rituals, and holistic care, which sometimes intersected with settler medicine,

Old West medicine was not the lucrative pursuit that doctors enjoy today. On the frontier, doctors typically charged 25 to 50 cents for a visit, with longer visits, including overnight stays, running up to a dollar. Fractures cost $2 to $10 to set, and delivering a baby was $4. However, many pioneers had no cash, with the average working-class household made only about $10 per week. In lieu of cash, patients often bartered for their care by feeding the doctor’s horse or offering produce, services, or goods of their own in payment.

However Old West doctors made up for this by making and selling their own medicines from raw herbs, leaves, and roots. In some Old West towns, the physician also served as the druggist due to the lack of qualified professionals in the community. Drugstores often stocked leeches that doctors used to bleed patients.

Old West doctors often used poultices (soft, moist masses of material such as bread, herbs, and clay material which were applied to the body) to treat wounds, draw out infection and promote healing. Poultices were believed to have anti-inflammatory and antiseptic properties. While some ingredients did have medicinal benefits, the effectiveness of poultices varied widely depending on the materials used and the condition being treated.

Cauterization, (burning a wound to stop bleeding and prevent infection) was a common medical procedure across the Old West. Doctors used heated metal instruments or chemicals to seal wounds (similar to cattle branding), a method that was both painful and risky. Despite its drawbacks, cauterization was often effective in controlling bleeding and preventing infections in an era before antibiotics. It was especially useful for gunshot wounds and mining and ranching injuries.

Infectious diseases were another formidable challenge to old West doctors. Epidemics of cholera, smallpox, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, and dysentery regularly ran rampant through frontier populations. The conditions in many boomtowns and mining camps—marked by overcrowding, poor sanitation, and limited clean water—created ideal environments for the spread of these illnesses.

Even trained doctors resorted to blood-curdling procedures when faced with no other option. One legend tells of a physician who “…slit the throat of the child choking with diphtheria, opening the windpipe and kept it open with fishhooks.”

Even trained doctors resorted to blood-curdling procedures when faced with no other option. One legend tells of a physician who “…slit the throat of the child choking with diphtheria, opening the windpipe and kept it open with fishhooks.”

Many pioneers believed the most effective medicine was the one that had the most disgusting taste. As a result, some doctors recommended drinking sulfur to treat illnesses.

Other Old West doctor wisdom. How to treat:

Cuts

• Pack the cut in axle grease.

• Take a large army ant and apply it to the cut so that the ant takes hold of each side of the wound with its pincers. Separate and remove its body, leaving the head to hold the cut together.

• Apply spider’s web to a bleeding cut.

• Pack the wound with gunpowder or wood ashes

Sore Throat

• Take a black thread, tie nine knots in it, and wear it around the neck for nine days.

• Heat coarse salt in a cast iron frying pan; fill a hand-knit wool stocking with the heated salt. Sew top of stocking together and hold it around the neck with a large safety pin.

• Tie a piece of fatback on a string and swallow the fatback, pulling it up again by the string. Repeat several times.

• To prevent catching strep throat, burn orange peels on the damper and inhale the fumes and smoke while they are burning.

• Mix turpentine from a fir tree with sugar and swallow it.

• Eat molasses candy made with a small amount of kerosene oil.

• Rub kerosene oil and butter on the throat and chest.

Snakebite

• Apply slabs of raw beef or chicken, or a mixture of vinegar and gunpowder.

About Nick Brumby

I like a good story. And of all stories, I love westerns the most.

As a kid, I spent far too many afternoons re-watching Clint Eastwood spaghetti westerns, picking up ‘Shane’ for just one more read, or saddling up beside Ben Cartwright when ‘Bonanza’ was on TV each afternoon.

I’m a former journalist and I love horses, dogs, and the occasional bourbon whiskey. I live with my wife, daughter and our ever-slumbering hound in a 1800’s-era gold mining town – our house is right on top of the last working gold mine in the area. There may not be much gold left, but there’s history wherever you look.

I hope you enjoy my westerns as much as I enjoyed writing them!

Happy trails,

Nick